The Italian painter Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) has long been regarded as a painters' painter - an artist passionately admired by other artists, but little known to the public. Of Morandi, the American painter and critic Fairfield Porter once wrote: ''More than any contemporary Italian painter's, his work has a quiet commanding authority. It is as though Cezanne had mellowed into a simplified serenity.''

On the occasion of the Morandi retrospective opening Friday at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum on Friday, The Times invited one of Morandi's artist-admirers to comment on his work. Mr. Thiebaud's own work has recently been the subject of a retrospective exhibition organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which is currently at the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art.

Whenever Giorgio Morandi's name is mentioned in the community of painters throughout the world, deep admiration and stunning tributes are expressed. What characteristics are responsible for a phenomenon of this dimension? The challenge to understand why is an opportunity for a personal reflection.

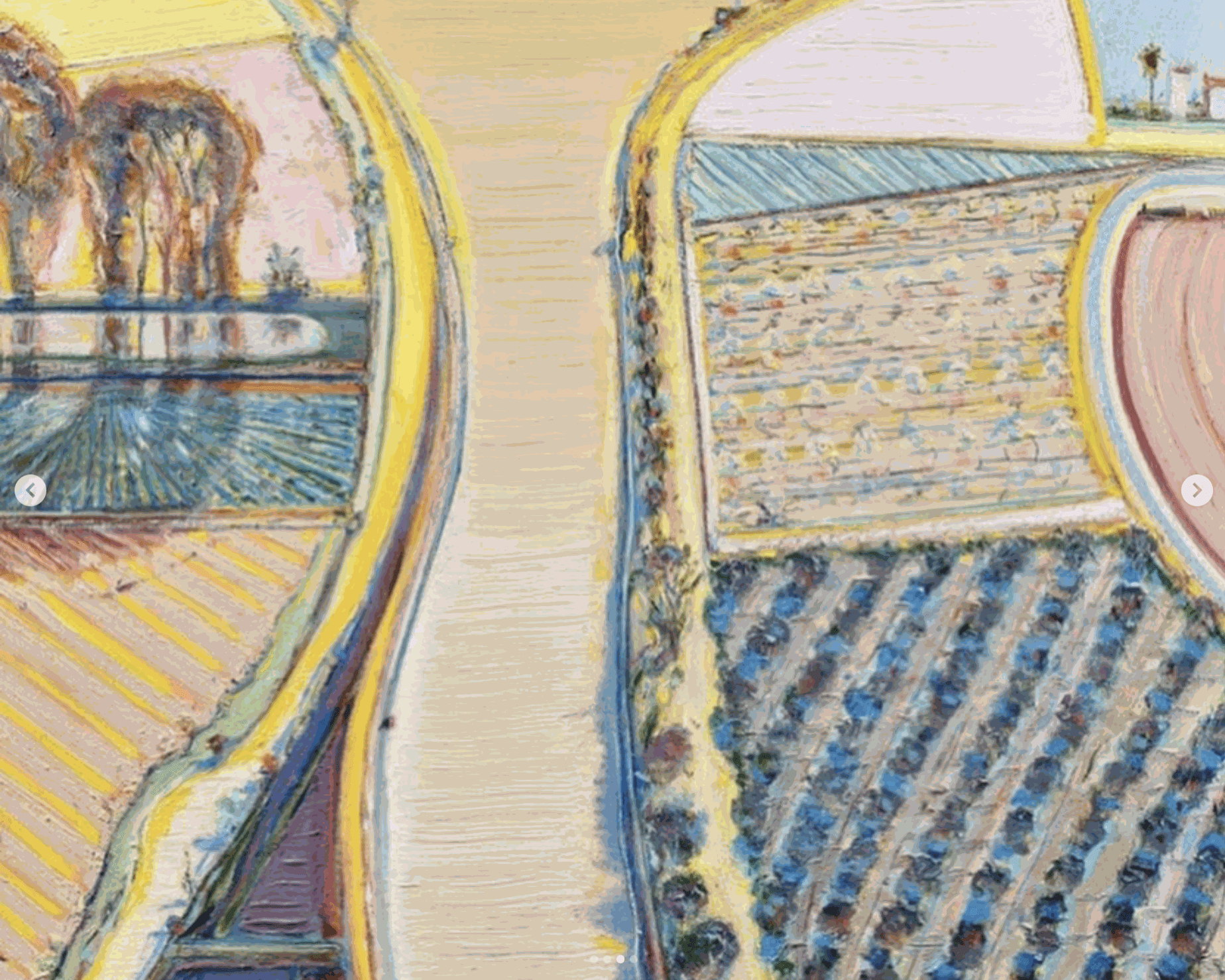

Wayne Thiebaud, Various cakes, 1981, oil on canvas

Shortly after World War II, in an art world richly celebrating iconoclasm, Morandi had the personal courage to embrace gnosticism, the alternative movement in religious thought which searched for substantial meaning in the world through inferences. Realizing the advantage of limitation as a means toward self-liberation, he turned to work in his bedroom-studio. Year after year that followed, on small rectangles and squares of canvas and paper, he painted and drew still lifes and landscapes. Slowly and carefully he began to externalize proof of his meditative skills. Modestly tracking his brushes with dirts and oils and hugging his rag (Morandi tended to use the rag as much as the brush in forming his configurations), he wove a kind of painted prayer rug. Illustrating his private flights through metaphysical speculations, he gave an intimate view of his deepest thoughts. We watched him inquiring after the devilish questions of essences and substance. Could they be expressed in painting? Morandi's capacity as a practiced and traditional disciplinarian allowed him to eloquently address questions of what makes poetry in painting.

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta, 1950, oil on canvas

Pedantically, this schoolteacher-painter showed us what it is to believe in painting as a way of life, to love its tattletale evidence of our humanness. Through an admixture of visual grammar and language his pictures reveal startling insights: what happens when gracefulness is juxtaposed against awkwardness? Is human ineptitude thereby understood, tolerated or ennobled? He juggles disproportionate but equal things and develops exquisite tensions. And how gently he can indicate tremendous vice-like pressures of an open space against a group of crowded forms. Adroit distinctions between size and scale is constantly tested by his choices of relationships, reflecting classic Platonic yearnings. In these grand little smearings, he plays with compositional orchestrations in a search for energetic geometrical models. In more lyrical works, a highlight may float and/or become porcelain. Often he makes a complex analysis of the simultaneity of form. That is, when a single colored slab or patch of paint, variously and at the same time, becomes the side of an object, its cast shadow, a table edge and the front of another bottle.