The revered Italian artist Giorgio Morandi made paintings that are mind-expandingly simple and complex at once. His still lifes of bottles arranged against neutral backgrounds—his favored mode of expression—strike some as boring but others as boundless in their charms. They’re the kind of paintings you can look at for ages while regaling in their quietude. And they’re the kind of paintings that make the pleasure of doing so feel like you’re looking at painting itself—the act, the result, the mysterious means of communication that can exude from a canvas.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1946. Courtesy Tate, 2020

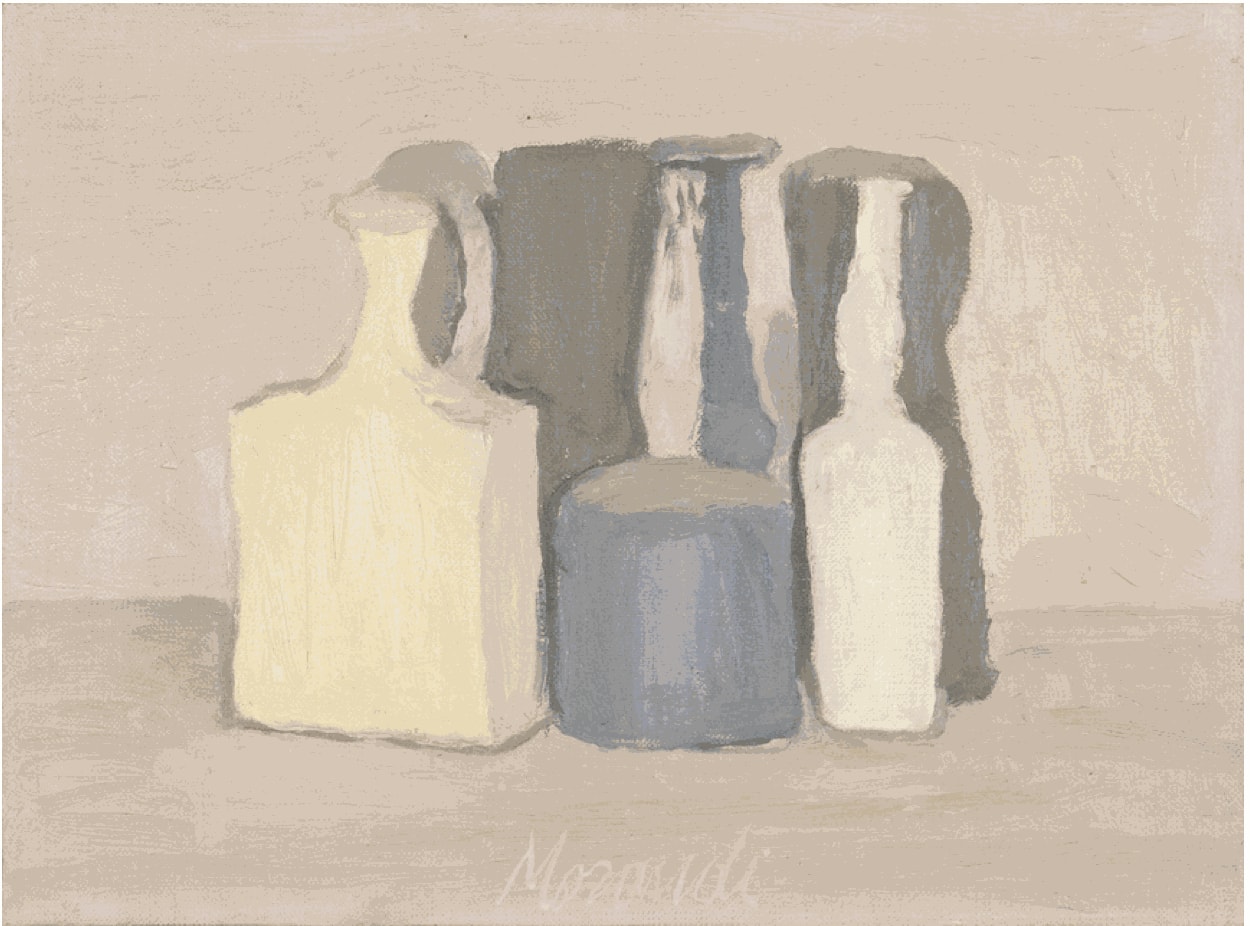

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1948-49. Courtesy Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Writing of his work in Giorgio Morandi 1890-1964: Nothing Is More Abstract Than Reality (the catalogue for an exhibition in 2008), Maria Cristina Bandera suggested, “It seems not to have left room for any of the uncertainty or crisis in which we easily recognize ourselves.” And the vaunted Italian art historian Roberto Longhi distilled it into more concrete terms, writing appreciatively of his “simple ‘objects,’ arranged, graduated, varied, exchanged.”

While Morandi’s reputation is secure among aficionados of art, he remains a singular and somewhat mystical figure not closely affiliated with any one movement or era. He seemed to work outside of time, in a world all his own, before his death in 1964 at the age of 73. Below are some lesser-known facts about an artist whose story can seem as secretive and meditative as the paintings he made.

He didn’t stray too far from home.

Perhaps appropriate for an artist whose vision was so up close and personal, Morandi was known to stay near to the city of Bologna—the site of his birth and death and home still to a museum devoted to his work as well as his preserved studio, which one can visit for the sake of soaking up its atmosphere. As chronicled in the monograph Morandi: 1890-1964, he only left Italy three times, all of them late in life, and within his home country he tended toward visits to nearby countryside resorts, where he worked on a style of landscape painting that figured in the paintings of bottles and jugs with which he’s most closely associated.

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1949. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art 2020

He was really into Impressionism.

Along with his centuries-old countrymen active during of the Renaissance, Morandi held out special affection for Impressionist painters whose ethereal visions influenced his style for sure. Tracing a lineage after the prime of Giotto and Masaccio, he wrote, “Among the moderns I believe Corot, Courbet, Fattori, and Cézanne to be the most legitimate heirs of the glorious Italian tradition.” And his liking of Cézanne is especially evident in paintings that often seem skewed but just a little bit—like a vision seeing a vision of itself while wondering what might be off in the periphery.

He is beloved by architects.

“After all, even a still life is architecture,” Morandi once said of a mode of painting for which he would arrange and rearrange similar-seeming objects as an imaginative city planner might. The objects he revisited were plainer than plain, but the interactions between them could turn into intricate affairs, with subtle treatments of texture and color adding extra emphasis to what could stand like city skylines in a language all their own. In a letter, a friend once wrote to Morandi expressing affection from noted architect Oscar Stonorov, and added, “Stonorov said Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, Gropius et al. also know and admire you.” (The others in the list were Bauhaus stars.) Frank Gehry also cited Morandi as inspiration for a wildly designed house he conceived in Wayzata, Minnesota.

Filmmakers are among his fans too.

Morandi’s work was a source of fasciation for feted film directors in Italy. Federico Fellini featured his work in La Dolce Vita, and Michelangelo Antonioni did the same in La Notte. His work was also in art collections belonging to Carlo Ponti (the storied movie producer and husband of Sophia Loren) and Vittorio De Sica (director of the timeless classic Bicycle Thieves).

He taught drawing to school kids.

In 1914, the same year he had a brief sort of dalliance with the Italian Futurist movement, Morandi started teaching drawing in elementary schools in Bologna—a post he continued until 1930.

He figures in a Don DeLillo novel.

The kinds of thoughts occasioned by artworks by Morandi meld well with the quiet searching style of late-period Don DeLillo, whose 2007 novel Falling Man makes a recurring figure of Morandi in a story set in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on New York’s World Trade Center. At one point a character goes to see a Morandi show at a gallery and finds some drawings to peer into. “She examined the drawings,” DeLillo writes. “She wasn’t sure why she was looking so intently. She was passing beyond pleasure into some kind of assimilation. She was trying to absorb what she saw, take it home, wrap it around her, sleep in it. There was so much to see.”

His studio objects are the subject of some great photographs.

In 2015, photographer Joel Meyerowitz published Morandi’s Objects, a book comprising pictures he took of bottles, vases, pitchers, jugs, blocks, and other stuff still retaining a special aura in the artist’s studio in Bologna. Writer Maggie Barrett (who also happens to be Meyerowitz’s wife and close collaborator) wrote in an introduction: “Having lived with Joel Meyerowitz for twenty-five years, I have come to discover, to some degree, his mystery, but in spite of having looked hard at Morandi’s paintings for thirty-five years, the man himself remains an enigma, not only to me, but also to those who knew him.”